Intuitively it seems that for an action to be free and for the agent performing the action to be held responsible for it, that agent must have the ability to do otherwise. In other words, to satisfy an assertion of freedom of action and agent responsibility the agent must be able to perform the action and be able to not perform the action. But Harry Frankfurt argues against this line of thought; he argues that the ability to do otherwise is not a necessary condition for having a free and morally responsible action. He says, “…the principle of alternate possibilities is false. A person may well be morally responsible for what he has done even though he could not have done otherwise. The principle’s plausibility is an illusion, which can be made to vanish by bringing the relevant moral phenomena into focus.” (156)

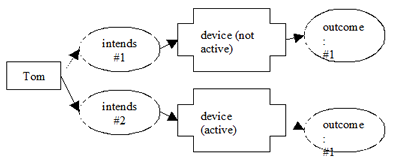

One example of a Frankfurt-style situation in which an agent is thought to be free and held morally responsible for performing an action is the “voting example”. In the voting example an agent, Tom, goes to the polls on election day to vote for either candidate #1 or candidate #2. In this case Tom intends to vote for candidate #1. Unbeknown to him, Tom’s evil neighbor had crept into his bedroom the night before and had implanted a device in Tom’s brain that would alter his choice if he had decided to vote for candidate #2 and not for #1. But since Tom intended to vote for #1 the device was never activated and thus, never affected Tom’s vote, his freedom, or his moral responsibility for casting his vote in the way that he did. So, in effect, Tom could not do otherwise but is still free and morally responsible.

At first glance it seems that Frankfurt has succeeded in showing that the ability to do otherwise is not a necessary condition for freedom and moral responsibility, but the example must be criticized in several places.

First, what exactly is meant when by the phrase “the ability to do otherwise” and more precisely, “do”? I think there are many ways to interpret this (Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary offers fifty-seven definitions), but it basically comes down to two. The first involves “do” referring to an action or a movement, like someone going to the polls to cast a vote. In this sense “the ability to do otherwise” would be to not go to the polls or to not cast a vote (for candidate #1, #2, or at all).

The second incorporates a teleological element into the equation, i.e. the reason for casting the vote, or more generally, the intended results of an agent’s action. In this sense “the ability to do otherwise” would be to have one’s intentions of casting a vote for #2 instead of #1 realized.

To apply these two different definitions to the example and to see their differences, it would help to visualize the cause and effect process of Tom in the voting booth. To review, Tom intends to vote for candidate #1. Tom’s evil neighbor also wants Tom to vote for #1 and has implanted a device in Tom that assures this (if Tom intends to vote for #2). But since Tom has no intention of voting for #2 the device is not used, Tom is free, bears moral responsibility and so on.

A schematic of the situation (fig. 1) allows one to easily visualize what is happening inside the mind of Tom and the results of it. The first set of ovals represents Tom in a primary mental state, in his intentions to vote for either candidate #1 or #2. It seems evident that everyone would agree Tom is free in this situation since he can vote for either #1 or #2 and is not yet affected by the implanted device. The problem arises when this primary information is perceived by the device and is then either ignored or translated into something else which leads to a different result than was intended. Now remembering the two interpretations of “the ability to do otherwise” and looking at (fig.1), it seems that Tom’s freedom and his moral responsibility may be in jeopardy.

His actions satisfy the first definition of “do” in that he acts on his own and chooses between two options, but the second definition is far from satisfied. Tom cannot act in a way that links his intentions with what will be the outcomes of those intentions in both cases. Only in the upper case does Tom have control of the outcome; in the lower case the device impedes his intentions and creates its own outcome. So it seems that the Frankfurt-style example, as used by Frankfurt, is incomplete in its analysis and in fact offers an example of freedom followed by an instance of lack of freedom. I believe this is why the example seems so paradoxical to a lot of people. From one perspective Frankfurt is correct, in that the agent cannot affect the result, cannot “do otherwise”. From another, more primary perspective the agent can “do otherwise”. The only problem is that the affect of the other action is not realized.

But this is not the end of the problem of free will and the ability to do otherwise. I believe that the common conception of freedom is highly problematic. Remember, the theory states that an action is free and the agent is responsible for the action if and only if the agent could’ve done otherwise. But this theory says nothing about the number of possible options open to the agent from which he can choose.

To continue let’s first define freedom and then we’ll look at our voting example again. “Freedom”, as defined by Webster’s is “the state of being free or at liberty rather than in confinement of under physical restraint” (763). I think most people would agree with this definition and would not find it problematic.

Now moving on to our voting example we said that Tom basically had three options open to him: (1) attempt to vote for candidate #1 (2) attempt to vote for candidate #2 and (3) don’t vote at all. What if Tom was not satisfied with these options? What if he wanted to vote for a third candidate or in a more extreme example, what if he wanted to get ice cream? This may not seem to make much sense at first, but bear with me.

Tom cannot escape the options given to him. He cannot act on options that do not exist. This is the situation in which we find ourselves every day and yet a lot of people believe they are free to act. But I perceive this as a limited freedom, a freedom that is bound by certain parameters. Webster’s definition, for example, spoke of being free of physical restraint. But what is physical restraint if not the laws of gravity and thermodynamics and space and, consequently, time? Breaking these laws are impossible and thus not available to us. But acting within these laws, within these absolute parameters I believe we can find a limited amount freedom. So the assertion that to have free will and to be held morally accountable for an action it is necessary that one have the ability to do otherwise is mistaken. We can’t jump to the moon or travel back in time, but yet we have a limited amount of freedom to choose from among the options that are available to us.

Figure 1:

All much too theoretical for me.

Agency is what one needs to consider with respect to free will and immediately one runs into difficulties because no one really knows what makes them do what they do. They may rationalise their decisions but they do not know what has made them rationalise them and, more than likely, their decisions are emotionally driven anyway and emotions are triggered in the subconscious, about which we know very little. To take a simple example, I do not know how I will finish this sentance until it appears in print.

More of this if you want.