Planting Seeds of Profit

Political Parties & Interest Groups

I. INTRODUCTION

The Shaping of an Industry

For two months in 1904, writer Upton Sinclair wandered the Chicago stockyards carefully noting the dead rats being shoveled into sausage-grinding machines, the bribed inspectors looking the other way as diseased cows were being slaughtered for beef, and the filth and guts that were being swept off the floor and packaged as “potted ham.” Less than two years later, he would author a book which would forever revolutionize inspection standards for the meat industry in the United States. Sinclair’s muckraking book, entitled The Jungle, incited a shocked public’s demand for reforms in the meat industry. By the end of that same year then President, Theodore Roosevelt, called upon Congress to pass a law establishing the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and, for the first time, set up federal inspection standards for meat. Remarking on his auspicious exposé, Sinclair claimed that, “It seemed to me that the walls of the mighty fortress of greed were at the point of cracking. It needed only one rush, and then another, and another.”

Where’s the Beef?

Some 100 years later, Upton Sinclair would certainly be alarmed at just how much mightier those walls of the fortress of greed have become. On the current state of the American beef industry, Howard Lyman, a retired cattle rancher turned president of a health and environmental advocacy organization exposed that the beef industry was feeding ground-up, diseased cattle to other cattle adding that “The current meat for sale to the U.S. consumer is more contaminated than their toilet” (Saaris 2004). Labeled an alarmist, Lyman has boldly joined the ranks of a growing number of muckrakers who believe that the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) has been neglectful in protecting the health and safety of those who consume farm products (Knickerbocker 2004).

The USDA is the regulatory agency responsible for ensuring the safety of U.S. beef products, but Title VII of the U.S. Code also gives it responsibility for “conducting beef promotion, research, and consumer education programs that are invaluable to the efforts of promoting the consumption of beef and beef products” (Saaris). As the organization charged both with promoting beef consumption and with providing independent food safety oversight of the meat industry, there is great potential for conflict of interest (Saaris). In addition to fundamental contradiction regarding responsibilities in the the meat industry, there are strong forces that may potentially be pulling the USDA in the direction of promotion at the expense of effective meatpacking regulation. Many contend that the level of influence which money has on the American political system tends to reduce zeal for effective regulation; the meat lobby has tremendous influence in Congress, and very, very deep pockets. For this matter, USDA whistleblowers have often claimed that inspectors are largely impotent when it comes to effective regulation (Saaris).

Franken Foods

Although it would seem that a public which has had “mad cow syndrome” inflicted upon it would be understandably uneasy about trusting science and agribusiness on any other matter pertaining to food, Franken foods have ironically become somewhat congruous to the American palate. While environmentalists worry about the effects of genetically modified organisms (GMO’s) in farmers’ fields, the loudest protests are coming from those who fear GMO’s on their dinner tables. They claim that while consumers can wash pesticides off their lettuce, what do they do when they’re inside the plant (Acosta 2000)? And while the FDA has determined that, so far, none of the GMO products on the market represents a threat to human health, consumer advocates feel that not enough careful, long-term research has been done to deliver a convincing conclusion. Caution, they contend, makes more sense than blind faith and that at a minimum, all foods containing GMO’s be labeled as such, so that the public can make an educated decision about what it eats (Acosta).

Keeping Pace

So, why the big fuss over veggies and meat? It is estimated that over the next 25 to 30 years the world population will increase by at least 2 billion. Astonishingly, about 95 percent of this growth is projected to occur in developing nations where nearly 800 million people are already undernourished. With global population growth soon promising to outpace food production, some argue that genetic engineering can help feed multitudes and expand crop productivity by as much as 25 percent and that the meat industry, now mechanized and consolidated, can more sufficiently and safely meet public demands. Keeping in step with this potentiality, American entrepreneurs have been leading the way in GMO research and marketing as well as in juggling public health concerns with big business interests in the beef industry. In this paper I will examine the use of GMO’s and its implications within the American agricultural and political sectors. In addition to analyzing the overall impact of biotechnology, I will also examine America’s flourishing beef industry and attempt to uncover how, if at all, business politics has played a role in augmenting public health standards.

II. HYPOTHESIS

In this paper I expect to find an industry which has outgrown the political sphere which was intended to regulates it and a political system which is incapable of adjusting to the over zealous business men which now run American agriculture. I also expect to find an industry whose rating as having the most sub par food standards of all developed countries, is attributable only to its overriding desire to turn a profit and to globalize its monopolistic business practices. I will invariable also find evidence that significant amounts of traceable money has been contributed to political candidates and parties as a means of maintaining industry dominance and ultimately political sovereignty.

III. DISCUSSION

Let Them Eat Steak!

Food security eludes an estimated 30 million Americans who suffer from chronic under consumption of adequate nutrients. But, even before the recent welfare cuts, food security for many Americans was eroding as cases of hunger have increased by 50% since 1985 (Allen). With a lack of access to food being closely linked to poverty, it has been found that between 1989 and 1993, a 26% increase occurred in the number of children living in families with incomes below 75% of the poverty line (Allen). However, despite poor people’s worsening economic conditions, policymakers began cutting food programs in the 1980s. The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 made substantial cuts to the three largest social-welfare programs in the United States: Aid to Families with Dependent Children, Supplemental Security Income, and the Food Stamp Program (Allen). Fully half of the budget savings from the 1996 welfare bill comes from reduced expenditures for the Food Stamp Program, which had been the primary source of food assistance for the poor. Additionally, another $2.9 billion in savings has been realized by cuts to child-nutrition programs (Allen). And, although policymakers say that private charity mitigates these cuts, contributions with that much breadth are unrealistic. A recent study estimated that even if the nation’s largest emergency-food network continues to expand at its average rate, it would only cover less than 25% of the food shortfall resulted from food-stamp cutbacks. This is particularly disturbing in light of the fact that 17% of requests for emergency food already go unmet. In instituting the largest cutbacks since food programs were first established in the United States, policymakers are clearly rejecting the notion that federal policy should provide a safety net against hunger (Allen).

What they are establishing, however, are significant benefits for agribusinesses and certain groups of individuals within the agricultural sector who wield some form of political clout. One measure of big business’ influence over the food and agricultural industry is their financial prominence in Congress. Agricultural interests contributed a whopping $24.9 million to presidential and congressional candidates in the 1991/92 elections alone. This breaks down to an average of $76,000 for each member of the House agricultural committee and $123,000 for each member of the Senate agricultural committee (Allen). Not surprisingly, these contributions were 50 times greater than those from groups promoting either health and welfare or children’s rights. While nearly all food and agriculture committee contributions come from producers, business, and industry, only a very small amount comes from consumer or labor groups. Interestingly, agricultural firms are dependent financially on federal agricultural policies so they can allocate time and money for lobbying efforts as a cost of doing business. While the hungry, who by definition are poor and therefore cannot generate vast sums of money to lobby or to make contributions with, must rely on groups representing their interests. These groups tend to be few, small, poorly funded, and unable to lobby on behalf of more than a few policies per year — clearly, no match for deep-pocketed agricultural interests.

Agribusiness: The Breeding of a Cash Cow

It is estimated that cattle interests alone have given more than $20 million to political campaigns since 1990, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. Although the Good Old Party (GOP) has received about 80 percent of the total contributions, Democrats and Republicans alike, most from farm and ranching states, have been recipients (Knickerbocker). Agribusiness’ presence is not just external; many top Bush appointees in the USDA have come from the industry. Secretary Ann Veneman’s chief of staff is the former chief lobbyist for the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, which is one of Washington’s most powerful special-interest groups. Even the department’s spokeswoman was the trade group’s director of public relations (Knickerbocker). Some say that having former beef- industry officials in senior positions brings a high level of expertise to the job, but critics maintain that it has been industry influence which has led to defeats for federal-budget increases aimed at vamping up inspections, loopholes in the FDA’s 1997 ban on the use of cattle remains as an ingredient in feed for ruminants (cows, goats, and sheep), and a refusal (until recently) to restrict the practice of allowing “downed” cattle (those injured or too sick to stand) as part of the food chain (Knickerbocker).

It comes as no shock that five years after its own 1997 ban, the General Accounting Office (GAO) criticized the FDA for laxness in policing the use of cattle remains to feed other livestock (Knickerbocker) warning that “Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE) may be silently incubating somewhere in the United States” (Knickenbocker). The GAO also warned that the FDA’s failure to enforce its own feed ban may have already placed US herds and, in turn, human food supply at risk (Knickenbocker).

Apart from the GAO, watchdog organizations like Safe Tables Our Priority contend that the USDA does not vigorously inspect the meatpacking process estimating that the United States’ current system leads to about 900 hospitalizations and 14 deaths a day from Campylobacter, E. coli, and Salmonella, with children facing the greatest health risks from meat-borne pathogens. Jan Lyons, a beef producer and president of a powerful beef industry lobby, the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, rebuffed these staggering estimations claiming that “everyone has a responsibility, including the consumer, producer, [and] all the way through that chain [for] food safety” (Saaris). Admittedly, many cases of meat-borne illness cannot be blamed on the producer or even on inspectors. Consumers, who may be naively uncritical in their meat selection, assume that the USDA Food Safety and Inspection Services is fulfilling its role by providing a regulatory check against the beef industry’s drive for profit. Tellingly, a certified USDA Meat Inspector named David Carney was quoted as saying that “We used to trim the s–t off the meat. Then we washed the s–t off the meat. Now the consumer eats the s–t off the meat” (Saaris).

Was Jack’s Bean Stalk a GMO?

Times are certainly changing, with most foreign markets anti-GMO, for the first time in modern history populations of the First World are serving as willing guinea pigs for populations of the Third World. And while pro-biotechnology scientists and firms adamantly claim that GMO products have been on the market for several years without a single reported case of adverse effects on human health, it has been argued that there are possible long-term impacts which may not become clear for some years. Also, potential environmental impacts will be particularly difficult to predict, monitor, and manage. As scientists readily admit, no technology is ever 100% safe, therefore, potential risks must be weighed against potential benefits (Clark 2002). But many assert that such risk/benefit analyses should be done at multiple levels: at a national level, by governments and regulatory agencies; at the production level, by farmers and firms; and at the individual level, by consumers. They continue, saying that at no point in this risk/benefit analyses should financial gain come into play.

While the first group of GMO’s introduced initially yielded benefits for commercial farmers, real profits were accrued by the firms that developed the seeds. Currently, GMO’s do not provide substantial financial benefits to any one group except its producers and market trends toward firm consolidation have further compromised the financial integrity of the farming industry in America. In attempting to enforce sound and equitable antitrust principles, the courts must consider economic issues of great variety and complexity. With the introduction of this new technology and the subsequent outgrowth of agribusiness conglomerates, the U.S. judicial system must distinguish between healthy business growth and the monopolistic tendencies that are beginning to shape the market. Whatever the outcome of this quandary, many contend that consumers will end up benefiting the least.

IV. ANALYSIS

The Meat and Potatoes of the Issue

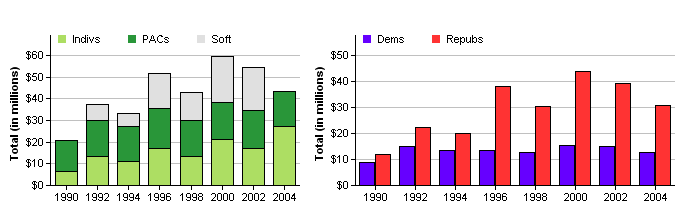

Shown below, figure 1 illustrates agribusiness’ astronomical amount of contribution over the past decade and a half to political parties.

Agribusiness: Long-Term Contribution Trends (figure 1)

| Election Cycle | Total Contributions | Contributions from Individuals | Contributions from PACs | Soft Money Contributions | Donations to Democrats | Donations to Republicans | % to Dems | % to Repubs |

| 2004* |

$43,367,529 |

$27,263,818 |

$16,103,711 |

N/A |

$12,575,392 |

$30,738,255 |

29% |

71% |

| 2002 |

$54,369,454 |

$17,241,919 |

$17,555,205 |

$19,572,330 |

$14,942,679 |

$39,378,227 |

27% |

72% |

| 2000 |

$59,431,442 |

$21,224,605 |

$17,264,638 |

$20,942,199 |

$15,439,178 |

$43,693,595 |

26% |

74% |

| 1998 |

$43,055,116 |

$13,222,619 |

$16,630,478 |

$13,202,019 |

$12,541,561 |

$30,521,429 |

29% |

71% |

| 1996 |

$51,591,480 |

$16,862,537 |

$18,682,368 |

$16,046,575 |

$13,529,473 |

$37,993,471 |

26% |

74% |

| 1994 |

$33,344,564 |

$10,933,647 |

$16,095,695 |

$6,315,222 |

$13,526,448 |

$19,938,579 |

41% |

60% |

| 1992 |

$37,156,700 |

$13,594,935 |

$16,273,698 |

$7,288,067 |

$14,930,491 |

$22,455,850 |

40% |

60% |

| 1990 |

$20,681,759 |

$6,689,204 |

$13,992,555 |

N/A |

$8,961,362 |

$11,803,200 |

43% |

57% |

| Total |

$342,998,044 |

$127,033,284 |

$132,598,348 |

$83,366,412 |

$106,446,584 |

$236,522,606 |

31% |

69% |

The steady rate of growth in contribution amounts over such a short period of time not only reflects a growing industry, but also one which is deeply invested in political support. Another point worth noting is that, among the top individual donors of all time to federal candidates and parties, Dwayne Andreas, Chairman of a large multinational company in the agricultural industry has donated the second most, closely trailing Peter Amstein of Microsoft Corporation.

Although the manner and effectiveness of lobbying varies among private interest groups, cohesiveness, size, prestige, financial resources, etc., allow some groups to wield a greater degree of influence than others. Similarly, the resources, style of lobbying, and effectiveness of the state agencies also play a large part in politically invigorating some industries over others. Overall, large corporations have grown to possess a disproportionate share of the world’s wealth. In fact, the 200 richest corporations of the world have resources equal to the cumulative wealth of the poorest 80% of the world’s population.

V. CONCLUSION

Because the current regulatory regime is characterized by big money, if consumers want to guarantee that American food is clean and healthy, we will have to use the tools of both the free market and of open democracy to apply economic and political pressure on the government and on the agribusiness industry. Enforcement mechanisms should be made more powerful, and a static line must be drawn clearly linking and defining public safety standards and government regulation. The science-based system of regulation put in place in the 1990s was a great step toward improvement but without the regulation of the regulators, the system of checks and balances will invariably break down.

Whatever the outcome of the biotechnology debate, it promises to be a long and grinding argument that will continue to pit agribusiness conglomerates against governmental health standards. Ultimately, America must choose between the inexorable forces of the market economy and the potential degradation of both our body’s and of our environments.

VI. WORKS CITED

Abney, Glenn. “Probing State and Local Administration Lobbying by the Insiders: Parallels of State Agencies and Interest Groups.” Public Administration Review .Vol. 48, No. 5. (Sep. – Oct., 1988), pp. 911-917.

Acosta, Anne. “Transgenic Foods: Promise or Peril?” Americas (English Edition) May 2000: 14.

Allen, Patricia. “Politics of Food and Food Policy: Contemporary Food and farm Policy in the United States.”

Knickerbocker, Brad. “Amending the US beef business: Greater consumer protections could result from heightened scrutiny of industry practices.” The Christian Science Monitor. January 07, 2004 edition

Saaris, Reid. “A Beef With Beef: Weak regulations put consumers of red meat at risk.” Harvard Political Review Online.

VII. BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abney, Glenn. Public Administration Review. “Probing State and Local Administration Lobbying by the Insiders: Parallels of State Agencies and Interest Groups” Vol. 48, No. 5. (Sep. – Oct., 1988), pp. 911-917.

Acosta, Anne. “Transgenic Foods: Promise or Peril?.” Americas (English Edition) May 2000: 14.

Buttel, H. Frederick; Martin Kenney; Jack Kloppenburg, Jr.. “From Green Revolution to Biorevolution: Some Observations on the Changing Technological Bases of Economic Transformation in the Third World.” Economic Development and Cultural Change. Vol. 34, No. 1. (Oct., 1985), pp. 31-55.

Cocheo, Steve. “Disappearing Harvest.” ABA Banking Journal 94.11 (2002): 41+.

Cocheo, Steve. “One More Whammy in a Harvest of Surprises?.” ABA Banking Journal 91.11 (1999): 31.

Goldberg, Ray A. “The Food Wars: A Potential Peace.” Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 28.4 (2000).

Nourse, G. Edwin. “Decisions: Desirable Public Policy.” Journal of Farm Economics. Vol. 44, No. 5 (Dec., 1962), pp. 1614-1623. “Politics of Food and Food Policy: Contemporary Food and farm Policy in the United States.”.

Strauss, Mark. “When Malthus Meets Mendel.” Foreign Policy. Summer 2000: 105.